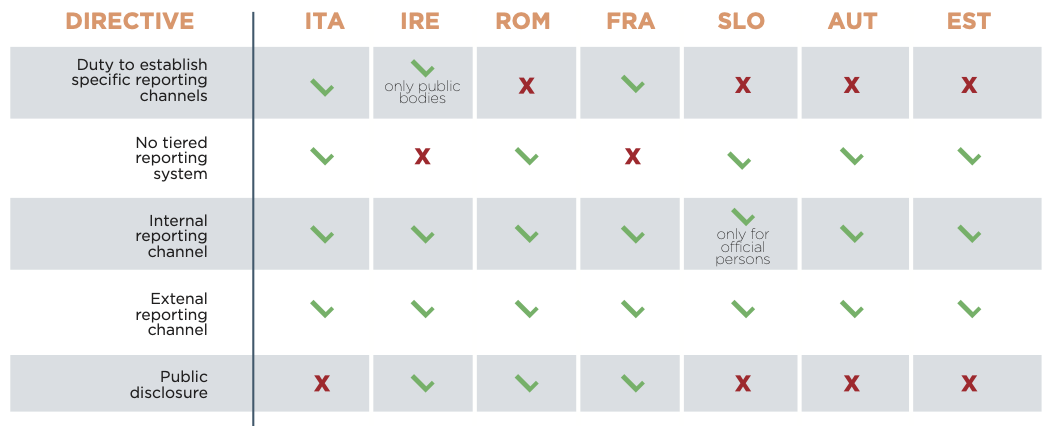

Whistleblowing in Italy, Austria, Estonia, France, Ireland, Romania and Slovenia

3. Reporting channels

The issue of reporting in stages was a highly debated

point in the decision-making process of the Directive.

In the final version, following the amendment proposed

by the European Parliament, the Directive leaves the whistleblower free to select the most appropriate reporting channel. However, it encourages reporting

through internal reporting channels before reporting

through external ones if the breach can be addressed

effectively internally and if the reporting person considers that there is no risk of retaliation.

Only Irish (just for the public sector), Italy and French

law provide the duty to establish internal reporting

channels.

- Italian law envisages the establishment of internal reporting channels for all public bodies and, in the private sector, only to those entities that have adopted the so-called 231 models. The adoption of these models is optional, but, if adopted, they must include one or more reporting channels and at least an alternative one with IT methods, which must guarantee the confidentiality of the whistleblower’s identity during the activities carried out in managing the report.

- France and Ireland have a tiered reporting system: whistleblowers must firstly disclose information internally; if this is not possible, or is inappropriate or ineffective, they may report to an external channel. In some circumstances, as a final step, it is possible to disclose publicly.

- In Slovenia, there is a similar reporting system but only for official persons reporting unethical conduct they have been requested. They may report such practices to their superior or the responsible person; if there is no responsible person, or if that person fails to respond to the report or if it is the responsible person himself/ herself who asks that official to engage in illegal or unethical conduct, the report will fall under the remit of the Commission.

- In Romania, a whistleblower may report to the hierarchical superior of the person who has breached the legal provisions, to the Head of the public authority, to the public institution or to the budgetary unit of the person who violated the legal rules. Furthermore, reports can also be made internally to the disciplinary commissions within the public institution to which the person who violated the law belongs.

In some countries, such as Italy, Romania and France,

it is possible to complain to a judicial authority. In Estonia and Slovenia, suspicions about corruption can be

reported to the Police.

In Austria, several public authorities provide reporting systems for whistleblowers, targeting specific areas. The BMI (Bundesministerium für Inneres), the Austrian Ministry of the Interior, focuses on reports on corruption and malpractice (in office); the WKStA (Wirtschafts und Korruptionsstaatsanwaltschaft), the Economic and Corruption Prosecutor, provides a full reporting system, with emphasis on corruption, criminal economic matters, social benefit fraud, balance and capital market offences and money laundering; the FMA (Finanzmarktaufsicht), the Financial Market Supervision Authority in Austria, deals with violations of compliance with the regulations by companies; the BWB (Bundeswettbewerbsbehörde), the Federal Competition Authority specialises in antitrust violations and cases of abuse of market power.

Only Romania and Ireland specifically envisage the possibility of public disclosure. In France, this is only possible as a last resort after the failure of the first two steps or in the event of “grave and imminent danger”. However, the Slovenian Integrity and Prevention of Corruption Act states that reporting to the Commission will not encroach on the reporting person’s right to inform the public of the corrupt practice.