Overview of whistleblower protection

| Sito: | Mooc |

| Corso: | M.o.o.c. Woodie - Whistleblower & Open Data |

| Libro: | Overview of whistleblower protection |

| Stampato da: | Utente ospite |

| Data: | lunedì, 8 dicembre 2025, 22:17 |

1. The whistleblowing phenomenon

Whistleblowers are persons who report, within the organisation concerned or to an outside authority, or disclose, to the public, information on wrongdoings carried out in a work-related context, whether private or public, big or small. They are essential players in national and global efforts to detect and prevent corruption and other malpractices that may otherwise remain hidden.

However, they are often discouraged from reporting their concerns for fear of retaliation: they may

lose their jobs, harm their career prospects, and even put their own lives at risk.

Whistleblower protection currently available across Europe is fragmented:

- At the EU level, before the Directive's approval, whistleblower protection was provided only in specific sectors (mostly just in the financial services area), and to varying degrees. This fragmentation and these gaps meant that whistleblowers were not adequately protected against retaliation in many situations. If potential whistleblowers do not feel safe in coming forward with the information they possess, this results in underreporting and therefore ‘missed opportunities' for preventing and detecting breaches of Union law which may cause serious harm to the public interest.

- In the Member States whistleblower protection is granted with uneven policy areas: most of them do not have dedicated legislation in place; the few countries with dedicated legislation present major loopholes and fall short of good practice. For example:

- Cyprus and Latvia do not have any form of protection for whistleblowers;

- Austria, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Finland, Croatia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Slovenia restrict protection to specific sectors (for example, public, private, banking/financial, etc.); Belgium and Spain limit it to part of the territory;

- France, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Malta, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Sweden and Slovakia have a single horizontal law for protecting whistleblowers;

- Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Greece, Lithuania and Romania have no provision for protection for private sector employees who report. Only partial protection is guaranteed - being provided only to employees in the financial and banking sectors - in Austria, Germany, Denmark, Finland and Poland;

- in Estonia and Finland there are no legal safeguards against retaliatory measures, while in Austria, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, Greece, Croatia, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal and Romania whistleblowers are protected only against specific retaliatory measures adopted in a working environment (dismissal or discrimination);

- the protection of confidentiality of the informant's identity is not guaranteed in Germany, Greece, Luxembourg and Sweden, while Bulgaria, Spain and Portugal limit this protection to specific sectors.

Lack of effective whistleblower protection could have negative impacts:

Lack of effective whistleblower protection could have negative impacts:

- on the freedom of expression and the freedom of the media, enshrined in Article 11 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights;

- on the application of EU law: whistleblowing is a means of providing national and EU enforcement systems with information, leading to effective detection, investigation and prosecution of breaches of Union rules;

- on the proper functioning of the single market.

2. International instruments and guidelines

International institutions such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

(OECD) and the Council of Europe have repeatedly pointed out that adequate protection of

whistleblowers is a critical tool for addressing corruption and malpractice and for protecting the

financial interests of the European Union. There have been several interventions aimed at urging

States to adopt specific regulatory provisions on whistleblowing, and some protection standards have

been included in international instruments and guidelines:

- the OECD’s “Recommendation on Improving Ethical Conduct in the Public Service, including Principles for Managing Ethics in the Public Service”, of 1998 (article 4);

- the Civil Law Convention on Corruption issued by the Council of Europe on November 4, 1999, which required the Member States to introduce adequate protection mechanisms for employees who, in good faith, report corruption (article 9);

- the United Nations Convention against Corruption of 31 October 2003, which requires the Member States to provide protection mechanisms for people who report facts of corruption (article 32 and 33);

- the OECD “Recommendation of the Council on Guidelines for managing conflict of interest in the public service” of 28 May 2003, which includes general principles to encourage the adoption by States of WB procedures that provide, on the one hand, the protection of whistleblowers from retaliation and, on the other, rules to prevent any abuses of the reporting mechanisms;

- Council of Europe Civil (ETS No. 174) and Criminal Law (ETS No. 173) Conventions on Corruption of 2003;

- the Council of Europe Recommendation [CM/Rec(2014)7] of 30 April 2014, on the protection of Whistleblowers;

- 2015 United Nations Convention against corruption (article 33): “Each State Party shall consider incorporating into its domestic legal system appropriate measures to provide protection against any unjustified treatment for any person who reports in good faith and on reasonable grounds to the competent authorities any facts concerning offences established in accordance with this Convention”.

- the Council of Europe “Protection of Whistleblowers: a Brief Guide for Implementing a National Framework” of August 2016, which identifies three different categories: “open whistleblower”, whose identity is known; “confidential whistleblower”, known only by a small circle of subjects with control duties; “anonymous informants”, whose identity is unknown or covered by anonymity.

- Transparency International: International Principles for Whistleblower Legislation.

- Government Accountability Project: International Best Practices for Whistleblower Policies.

- Open Society Justice Initiative: Global Principles on National Security and the Right to Information (“Tshwane Principles”).

- Organisation of American States: Model Law to Facilitate and Encourage the Reporting of Acts of Corruption and to Protect Whistleblowers and Witnesses.

- OECD for G20: Study on G20 Whistleblower Protection Frameworks, Compendium of Best Practices and Guiding Principles for Legislation.

- Council of Europe: Recommendation on the Protection of Whistleblowers adopted by the Committee of Ministers in April 2014 CM/Rec(2014)7.

The European Court of Human Rights established that the protection of freedom of expression (article 10 ECHR) also extends to those persons (whistleblowers) who report to the dedicated authorities illegal behaviours occurring in the workplace, whether they are public or private employees.

Compare with the judgment Guja vs. Moldavia, no. 14277/14, sentence 12 February 2008.

2.1. EU initiatives

In its 5.7.2016 Communication, the  Commission underlined that protecting whistleblowers in the

public and private sector contributes to addressing mismanagement and irregularities, including crossborder corruption relating to national or EU financial interests.

Commission underlined that protecting whistleblowers in the

public and private sector contributes to addressing mismanagement and irregularities, including crossborder corruption relating to national or EU financial interests.

It stressed the need for effective measures to protect those who report or disclose information on threats or harm to the public interest, thus contributing to increased detection of fraud and tax evasion.

The Commission announced that it would have continued to monitor the Member States' provisions and to facilitate research and the exchange of best practices to encourage improved protection at national level. It also indicated that it was assessing the scope for horizontal or further sectoral action at EU level while respecting the principle of subsidiarity.

President Juncker affirmed the commitment to assess the scope for further action to strengthen the

protection of whistleblowers in EU law in the Letter of Intent complementing his 2016 State of the

Union speech and in the 2017 Commission Work Programme.

With its Resolution of 14 February 2017 on the role of whistleblowers in the protection

of EU’s financial interests (2016/2055(INI)), the European Parliament:

- called on the Commission to submit a legislative proposal before the end of 2017 protecting whistleblowers “as part of the necessary measures in the fields of the prevention of and fight against fraud affecting the financial interests of the Union, with a view to affording effective and equivalent protection in the Member States and in all the Union’s institutions, bodies, offices and agencies”;

- called on the Commission to carry out a public consultation to seek the view of stakeholders on the reporting mechanisms and the potential shortcomings of the procedures at national level;

- recognised that whistleblowers play an essential role in helping Member States, EU institutions and bodies to prevent and tackle any breaches of the principle of integrity and misuse of power that threaten or violate fundamental sectors;

- called on those Member States that had not yet adopted principles to protect whistleblowers in their domestic law to do so as soon as possible;

- emphasised that whistleblowing relating to the financial interests of the Union is the disclosure or reporting of wrongdoing, including, but not limited to, corruption, fraud, conflicts of interest, tax evasion and tax avoidance, money laundering, infiltration by organised crime and acts covering up any of these;

- pointed out that protection is granted to those who disclose information in the reasonable belief that the information is correct at the time it is revealed, including those who make inaccurate disclosures by genuine error;

- expressed the need to ensure that reporting mechanisms are accessible, safe and secure and that whistleblowers' claims are professionally investigated;

- called on the Commission, and on the European Public Prosecutor’s Office to set up effective communication channels between the parties concerned and, likewise, to establish procedures for receiving and protecting whistleblowers who provide information on irregularities relating to the financial interests of the Union, and to establish a single working protocol for whistleblowers;

- emphasised the need to protect the confidentiality of the information sources to prevent any discriminatory actions or threats;

- considered it necessary to foster an ethical culture that helps to ensure that whistleblowers do not suffer retaliation or face internal conflicts; it called for the Commission to provide a clear legal framework that guarantees that those exposing illegal or unethical activities are protected from retaliation or prosecution and to present concrete proposals for the full protection of those who disclose illegalities and irregularities;

- invited the EU agencies to provide a written policy on protecting whistleblowers from reprisals;

- drew attention to the fact that some existing schemes provide financial rewards to whistleblowers (such as a percentage of the sanctions ordered); considered that although this needs to be managed carefully to prevent potential abuse, such awards could provide significant income to persons who have lost their jobs as a result of whistleblowing.

Between 3 March and 29 May 2017, the European Commission carried out an open public consultation

(OPC) to collect views on the issue of whistleblower protection at national and EU level. The

Commission received 5,707 replies.

Between 3 March and 29 May 2017, the European Commission carried out an open public consultation

(OPC) to collect views on the issue of whistleblower protection at national and EU level. The

Commission received 5,707 replies.The results were as follows:

- almost all participants agreed on the need to protect whistleblowers (99.4%);

- 96% were in favour of introducing legally binding minimum standards on whistleblower protection in Union law;

- the majority of respondents (85%) believed that workers very rarely or rarely report concerns about threat or harm to the public interest;

- fear of legal (80% of individual respondents and 70% of organisations) and financial consequences (78% of individual respondents and 63% of organisations) and fear of a bad reputation (45% of individual respondents and 38% of organisations) were the reasons most widely cited as to why workers do not report wrongdoings.

In its Resolution (2016/2224, 24 October 2017) on legitimate measures to protect whistleblowers acting in the public interest when disclosing the confidential information of companies and public bodies, the European Parliament:

- called on the Commission to present before the end of the year a horizontal legislative proposal establishing a comprehensive common regulatory framework which guarantees a high level of protection across the board, in both the public and private sectors, as well as in national and European institutions, including relevant national and European bodies, offices and agencies, for whistleblowers in the EU, taking into account the national context and without limiting the possibility for the Member States to take further measures;

- pointed out that relevant EU legislation should establish a clear procedure for properly handling disclosures and effectively protecting whistleblowers;

- considered ‘whistleblower’ to mean anybody who reports or reveals information in the public interest, including the European public interest;

- deplored the fact that only a few Member States had introduced sufficiently advanced whistleblower protection systems;

- believed that it was necessary to introduce protective measures against retaliation. It stressed that, once someone is recognised as a whistleblower, steps should be taken to protect him or her, to bring to an end any retaliation measures taken against him or her, and to grant the whistleblower full compensation for the prejudice and damage incurred. Whistleblowers should not be liable for prosecution, civil legal action or administrative or disciplinary penalties due to making the report;

- in relation to whistleblower protection, it believed that, where applicable, psychological support should be provided, that specialised legal aid should be given to whistleblowers who request it and lack sufficient resources, that social and financial assistance should be given to those who express a duly justified need for it and as a protective measure if civil or judicial proceedings are brought against a whistleblower, in accordance with national law and practices. It added that compensation should be granted, irrespective of the nature of the damage suffered by the whistleblower as a result of making a report. Moreover, it emphasised that whistleblowers must be guaranteed proper reception arrangements, accommodation and safety in a Member State which does not have an extradition agreement with the country that committed the acts in question;

- called on the Member States and EU institutions, in cooperation with all relevant authorities, to introduce and take all possible necessary measures to protect the confidentiality of the information sources in order to prevent any discriminatory actions or threats, as well as to establish transparent channels for information disclosure, to set up independent national and EU authorities to protect whistleblowers, and to consider providing those authorities with specific support funds. It also called for the establishment of a centralised European authority for the adequate protection of whistleblowers and people who assist their acts based on the model of national privacy watchdogs. It called on the Commission, for these measures to be effective, to develop instruments focusing on protecting against unjustified legal prosecutions, economic sanctions and discrimination.

3. The proposal for a Directive

The Commission’s proposal for a Directive (23 April 2018) set out minimum standards for whistleblower protection in areas with a clear EU dimension and where the impact on enforcement is the strongest.

The proposal introduced solid protection for whistleblowers who report violations in sectors where:

- violations of EU law may cause serious harm to the public interest,

- a need to strengthen enforcement has been identified,

- whistleblowers are in a privileged position to disclose infraction.

The proposal focused on the areas of public procurement; financial services; prevention of money laundering and terrorist financing; product safety; transport safety; environmental protection; nuclear safety; food and feed safety, animal health and welfare; public health; consumer protection; protection of privacy and personal data, and security of network and information systems.

In several of them (such as financial services, aviation safety and maritime transport safety) the EU legislator had already set up specific channels for reporting a violation and protecting those who make such a report.

Where already offered, the proposed Directive supplemented this protection with additional provisions and safeguards.

The Proposal strove to ensure that:

- potential whistleblowers have clear reporting channels available to report both internally (within an organisation) and externally (to an outside authority);

- when such channels are not available or cannot reasonably be expected to work correctly, potential whistleblowers can resort to public disclosure;

- the competent authorities are obliged to follow up diligently on reports received and to give feedback to whistleblowers;

- retaliation in its various forms is prohibited and punished;

- if whistleblowers do suffer retaliation, they have easily accessible advice free of charge;

- they have adequate remedies at their disposal (e.g. interim remedies to halt ongoing retaliation such as workplace harassment or to prevent dismissal pending the resolution of potentially protracted legal proceedings);

- reversal of the burden of proof, so that the person taking action against a whistleblower must prove that it is not retaliating against the whistleblowing act.

Aspects to be improved according to Transparency International to ensure comprehensive and effective protection to whistleblowers in line with international standards and best practices:

- The motives of a whistleblower in reporting information that they believe to be true should be unequivocally irrelevant to the granting of protection [articles 13 and 17 of the proposed Directive];

- employees should be able to report breaches of law directly to the competent authorities;

- the whistleblower's identity should be more effectively protected [articles 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 and 17];

- the Directive should address anonymous reporting;

- whistleblowers should be entitled to full reparation through financial and non-financial remedies;

- the reversal of the burden of proof should be strengthened;

- national whistleblowing authorities should be responsible for the supervision and enforcement of whistleblowing legislation;

- penalties should be extended to all situations where obligations under the Directive are not fulfilled [article 17];

- the material scope should be extended as much as possible;

- the personal scope should be extended to include former employees, EU staff and persons associated with a whistleblower or believed to be a whistleblower [article 2].;

- all public-sector entities should be obliged to establish internal reporting mechanisms [article 4];

- internal reporting mechanisms should provide for transparent, enforceable and timely procedures to follow up on whistleblowers’ complaints of unfair treatment [chapter II of the proposed Directive];

- internal reporting procedures should include an obligation to acknowledge receipt of the report [articles 5 and 11];

- the collection and publication of comprehensive data on the functioning of reporting mechanisms should be mandatory for both internal and external reporting (at least in the public sector) [article 21];

Impact assessment accompanying the Proposal for a Directive

Four policy options had been assessed and two options had been discarded. The preferred one was a Directive with a broad scope, particularly apt for addressing the current fragmentation and for enhancing legal certainty so as to address effectively underreporting and to enhance the enforcement of Union law in all the identified areas, where breaches could cause serious harm to the public interest. The legislative initiative was complemented by a Communication setting out a policy framework at EU level, including measures to support national authorities.

Benefits of the Directive:

- It supports national authorities in their efforts to detect and deter fraud and corruption in detriment to the EU budget (the current risk of loss revenue is estimated to be between EUR 179 billion and EUR 256 billion per annum).

- In other areas of the single market, such as in public procurement, the benefits are estimated to be in the range of EUR 5.8 to EUR 9.6 billion each year for the EU as a whole.

- It effectively supports the fight against tax avoidance resulting in loss of tax revenues from profit-shifting for the Member States and the EU, estimated to be about EUR 50-70 billion per annum.

- The introduction of robust whistleblower protection improves working conditions for 40% of the EU workforce who are currently unprotected from retaliation measures and will increase the level of protection for nearly 20% of the EU workforce.

- It enhances the integrity and transparency of the private and public sector, contributing to fair competition and creating a level playing field in the single market.

Implementation costs:

- for the public sector they are expected to amount to €204.9 million as one-off costs and €319.9 million as annual operational costs;

- for the private sector (medium-sized and large companies) the projected total costs are expected to amount to €542.9 million as one-off costs and €1016.6 million as annual operational costs. The total costs for both the public and private sector are €747.8 million as one-off costs and €1336.6 million as annual operational costs;

- costs for companies: micro and small companies are not obliged to put in place internal reporting channels. The general exemption of small and micro-companies does not apply to companies active in the area of financial services or vulnerable to money laundering or terrorist financing. Small and micro companies operating in the area of financial services are not exempted from the obligation; the cost for those companies is minimal (sunk costs) since they are already obliged to establish internal reporting channels under existing Union rules.

3.1. The whistleblowers Directive

On 16 April 2019, the European Parliament voted in an overwhelming majority to adopt the Directive.

The Directive was adopted on 23 October 2019 and has a transposition deadline of 17 December 2021 (with the exception of the obligation to establish internal reporting channels with a further two-year extended deadline).

The adopted text marks a step forward compared to the Proposal, introducing additional guarantees for whistleblowers.

One of the most controversial points of the Commission Proposal was the three-tier reporting process: they were generally required to use internal channels first; if these channels did not work or could not reasonably be expected to work, they could have reported to the competent authorities, and, as a last resort, to the public. The European Parliament succeeded in changing this provision, leaving whistleblowers free to choose the most appropriate reporting channel, although public disclosure is still subject to certain conditions.

The most significant measures introduced by the Directive are:

- the boundaries of the term “retaliation” are better defined as “any direct or indirect act or omission which occurs in a work-related context prompted by the internal or external reporting or by public disclosure, and which causes or may cause unjustified detriment to the reporting person” (article 6);

- the Directive shall not affect the responsibility of the Member States to ensure national security and their power to protect their essential security interests. In particular, it shall not apply to reports on breaches of the procurement rules involving defence or security aspects unless they are covered by the relevant instruments of the Union (article 3);

- the personal scope (article 4) is extended to include also civil servants in the status of ‘workers' whose protection should be granted, shareholders and persons belonging to the administrative or supervisory body of an undertaking, paid trainees and persons whose workbased relationship ended. Protective measures of reporting persons who publicly disclose information on breaches falling within the scope of this Directive also apply to facilitators (persons who assist the whistleblower in the reporting process in a work-related context), third persons connected with the reporting persons and who may suffer retaliation in a work-related context, such as colleagues or relatives of the reporting person, and legal entities that the reporting persons own, work for or are otherwise connected with in a workrelated context;

- the motives of the whistleblower in making the report are irrelevant as to whether or not they should receive protection (recital 33);

- the decision to accept and follow up on anonymous reports of breaches falling within the scope of the Directive is left to the Member States, but full protection is granted to whistleblowers who have reported or made public disclosures anonymously and who have subsequently been identified and suffer retaliation (article 5);

- the reporting person can choose the most appropriate channel depending on the individual circumstances of the case. Even if the use of internal channels before external reporting is encouraged where the breach can be effectively addressed internally and where the reporting person considers that there is no risk of retaliation, persons shall provide information on breaches falling within the scope of this Directive externally or directly to relevant institutions, bodies, offices or agencies;

- public disclosures (article 15): if no appropriate action is taken in response to the internal and/or external report within the set timeframe or if the whistleblower believes that there is an imminent danger to the public interest or a risk of retaliation, the reporting person will still be protected if he/she discloses the information to the public;

- article 16 extends the duty of confidentiality: any information from which the identity of the reporting person may be directly or indirectly deduced shall not be disclosed to anyone beyond the authorised staff members competent to receive and/or follow-up on reports without the explicit consent of this person. It may only be revealed when this is a necessary and proportionate obligation required by Union or national law in the context of investigations by national authorities or judicial proceedings, in particular, to safeguard the rights of defence of the concerned person. In that case, the reporting person shall be informed (with a written justification explaining the reasons for the disclosure of the confidential data concerned) before his or her identity is disclosed, unless such information would jeopardise the investigations or judicial proceedings;

- any form of retaliation is prohibited, including threats and attempts of retaliation, whether direct or indirect (article 19);

- listing the particular forms that retaliation measures can take, the adopted text specifies that the failure to convert a temporary employment contract into a permanent one is relevant only if the worker had legitimate expectations that he or she would be offered permanent employment. It also adds psychiatric or medical references among the forms of retaliation;

- article 20 states that during legal proceedings whistleblowers may receive financial and psychological support and that supporting measures may be provided, as appropriate, by an information centre or a single and identified independent administrative authority;

- article 21 specifies that persons making a report or a public disclosure in accordance with this Directive shall not be considered to have breached any restriction on disclosure of information and shall not incur liability of any kind in respect of such reporting or disclosure provided that they had reasonable grounds to believe that the reporting or disclosure of such information was necessary for revealing a breach according to this Directive;

- in cases where the reporting persons lawfully acquired or obtained access to the information reported or the documents containing this information, they should enjoy immunity from liability;

- in relation to the burden of proof, article 21 states that in proceedings before a Court or other Authority relating to a detriment suffered by the reporting person, and subject to him or her establishing that he or she made a report or public disclosure and suffered a damage, it shall be presumed that the detriment was made in retaliation for the report or disclosure. In such cases, it shall be for the person who has taken the detrimental measure to prove that this measure was based on duly justified grounds;

- the safeguards also apply to persons assisting the whistleblower, such as facilitators, relatives or colleagues;

- the Member States shall take the necessary measures to ensure not only remedies but also full compensation for damages suffered by reporting persons at the conditions set in the Directive;

- appropriate remedies may take the form of actions for reinstatement (for instance, in case of dismissal, transfer or demotion, or of withholding of training or promotion) or for restoration of a cancelled permit, licence or contract; compensation for actual and future financial losses (for lost past wages, but also for future loss of income, costs linked to a change of occupation); compensation for other economic damages such as legal expenses and costs of medical treatment, and for intangible damage (pain and suffering);

- article 24 introduces a no waiver of right and remedies clause: the Member States shall ensure that the rights and remedies provided for under this Directive may not be waived or limited by any agreement, policy, form or condition of employment, including a pre-dispute arbitration agreement;

- article 25 adds a no regression clause: The implementation of this Directive shall under no circumstances constitute grounds for a reduction in the level of protection already afforded by the Member States in the fields covered by the Directive.

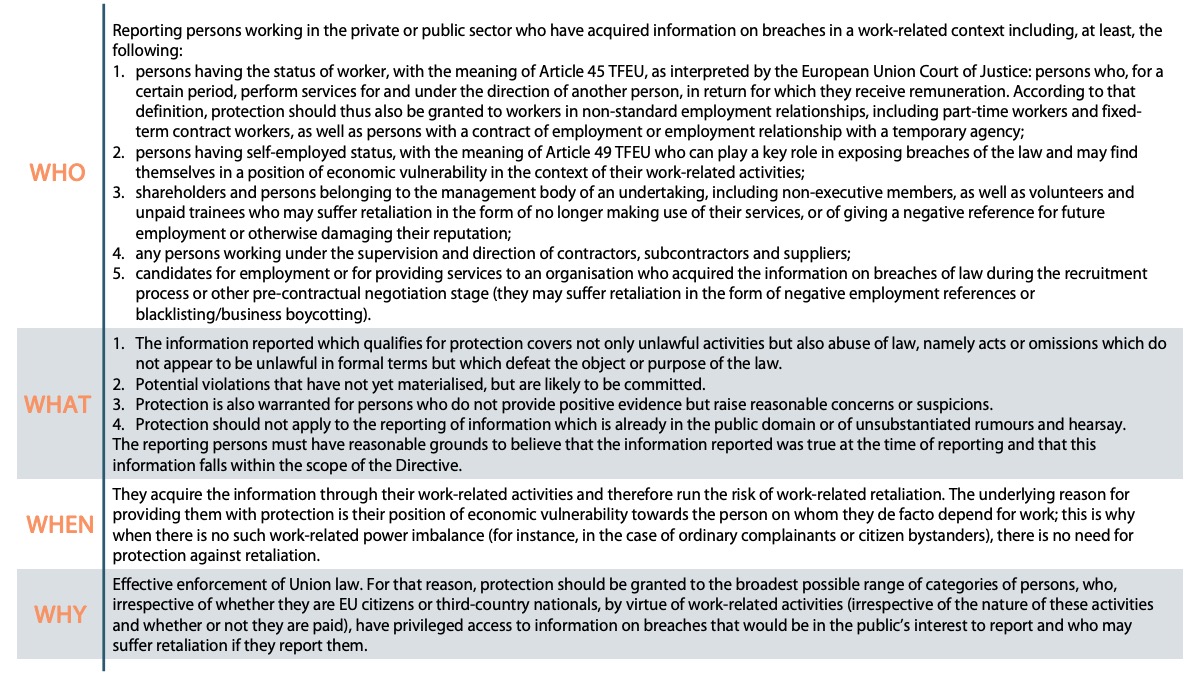

3.2. Summing up: whistleblower protection according to the Directive