Whistleblowing in Italy, Austria, Estonia, France, Ireland, Romania and Slovenia

| 站点: | Mooc |

| 课程: | M.o.o.c. Woodie - Whistleblower & Open Data |

| 图书: | Whistleblowing in Italy, Austria, Estonia, France, Ireland, Romania and Slovenia |

| 打印: | Utente ospite |

| 日期: | 2025年12月10日 星期三 04:50 |

1. Introduction

The purpose of this report is to provide a comparative analysis of whistleblower protection in seven EU Member States: Italy, Austria, Estonia, France, Ireland, Romania, and Slovenia.The analysis will be carried out taking account of the recent approval of the EU Directive on Whistleblower Protection, to highlight the existing national provisions which are in accordance to the Directive requirements and the efforts that countries still have to make in order to implement it.

Only three of the seven examined countries have a

national law dedicated entirely to whistleblower protection: Romania, Ireland and Italy. Among them, Romania is the forerunner, as its law dates back to 2004, while in Ireland and Italy the standalone legislation

on whistleblowing entered into force, respectively, in

2014 and 2017.

However, both in Ireland and in Italy, whistleblowers already received protection before the enactment of the law. In Ireland, there were several sector-based agreements which concerned members of the public, some of which remained in force. In Italy, the first provision ever intended to protect public sector whistleblowers from retaliation was introduced in 2012 by Anti-Corruption Law no. 190, and there are other rules dedicated to whistleblowing in specific sectors, which are still in force.

In other countries, protection is granted through more comprehensive laws or provisions in sector-based laws.

However, France must be distinguished among them. Although it does not have a law whose exclusive purpose is to protect whistleblowers, the so-called “Sapin 2 Law” includes a general statute for whistleblowers that applies both in public and private sectors and to all reports. The Sapin 2 Law coexists with different special regimes applicable according to the type of employment of the public official or the sector in which the alert is issued.

Both Estonia and Slovenia have an Anti-Corruption Law that only protects whistleblowers who report on corruption, although with a key difference. The Estonian Anti-Corruption Act has limited personal scope, as it provides protection only to public officials who report corruption regarding other public officials. Conversely, the Slovenian Integrity and Prevention of Corruption Act provides that anyone can report any kind of corruption. However, the Slovenian Act also gives specific protection to official persons who report unethical or illegal conduct they have been requested in their sphere of work. In both countries, other provisions within legal acts could apply to whistleblowers, although not envisaging them specifically.

Whistleblowers in Austria are only mentioned in the

Securities/Stock Exchange Act and corporate law.

Their protection is either limited to specific sectors or

for specific types of wrongdoing; other relevant

laws may apply.

Austria, Estonia, Romania and Slovenia do not have

designated soft law tools on whistleblowing, but in

Romania and Slovenia there are ethical codes, which

are only morally binding documents. Conversely, Italy, France and Ireland have soft law guidance

documents to support the effective implementation of

the law.

1.1. Definition

For most of the countries, a whistleblower is a person who reports information on breaches of which he/she has learned in the context of work-related activities.

For most of the countries, a whistleblower is a person who reports information on breaches of which he/she has learned in the context of work-related activities. This definition is part of the one given by the Directive, which adds, however, that whistleblowers are also those who make - in specific circumstances - a public disclosure.

However, it should be noted that in the Slovenian Integrity and Anti-Corruption Act, whistleblowers are referred to as “any person who reports instances of corruption”, regardless of whether knowledge of such corruption was acquired in the context of an employment relationship.

- in France and Romania whistleblowers are expressly defined by law;

- in Slovenia and Italy, they are only defined implicitly;

- Irish law does not define the whistleblower but the “protected disclosure”;

- in Austria and Estonia there is no special legal definition.

- Romania, Slovenia and France expressly require the whistleblower’s good faith. The latter also adds that the report must be made “in a disinterested manner”, while the Slovenian Act also requires the whistleblower reasonably to believe that the information, as provided, is true;

- in Ireland, as well as in the Directive, acting in good faith is seen to be acting in the reasonable belief that the disclosure is substantially true;

- in Italy, whistleblowers must report in the interest of the integrity of the public administration or the private entity.

The catalogue of breaches that may be reported is wide and varied. The Directive has adopted a broad notion of breaches falling within its scope, which also includes abusive practices, i.e. acts or omissions that do not appear to be unlawful in formal terms but which defeat the object or the purpose of the law.

- The Irish, Romanian and French laws provide a list of wrongdoings that may be reported, while in Italy, this is included in the Guidelines of the National Anti-Corruption Authority.

- Romania adds to violations of laws also the breach of professional ethics or the principles of proper administration, efficiency, effectiveness, economy and transparency, and expressly indicates a breach of legal provisions regarding public procurement.

- France also adds the possibility of reporting “a serious threat or prejudice to the general interest”.

- Conversely, the subject of the reports is somewhat limited in Slovenia and Estonia, where whistleblowers may only report corruption. Irish law specifies, like the Directive, that the reasons for disclosure are irrelevant.

1.2. Sector of application

Not all of the compared countries protect whistleblowers in both the public and private sectors, as required by the Directive.

- In Romania, whistleblower protection in the private sector is only voluntary, and in Estonia there are no specific forms of protection in the private sector.

- In Austria, private sector employees are protected only in the financial and banking sector. However, large enterprises and multinational companies started to implement internal whistleblowng systems to fulfil compliance procedures and good practice recommendations.

- In Italy, protection in the private sector has only been provided since the end of 2017 and, moreover, it only applies to those corporate entities and associations, including those which are not corporate bodies, that have established organisation and management models, known as “231 models”. The adoption of these models is optional, and they are aimed at excluding or limiting the liability of institutions for crimes committed by individuals in their interest or for their benefit. As far as the public sector is concerned, Italian law applies to public administrations, public economic entities and private law entities under public control in accordance with Art. 2359 of the Civil Code;

- Irish law applies to all public bodies, such as government departments, local authorities and certain other publicly-funded bodies, which are listed in the law . Rules concerning whistleblowers in Romania apply to public authorities and institutions of the central and local public administrations, apparatus of the Parliament, working apparatus of the Presidential Administration, working apparatus of the Government, autonomous administrative authorities, public institutions of culture, education and health, national state-owned companies, and other representatives of the public sector.

- In Slovenia, the scope of protection is very broad and extends to public companies and the state administration (state body, local community, a holder of a public authority or other legal persons governed by public or private law), as well as to private companies.

- French rules are in line with the provisions of the Directive since they apply without distinction to both the public and private sectors; the only difference concerns the thresholds provided for the duty to establish internal reporting channels and procedures for reporting.

2. Subjective field of application

The Directive provides an extensive personal scope,

which not only includes persons having the status of

worker, including civil servants, but also persons having

self-employed status, shareholders and persons belonging to the administrative, management or supervisory

body of an undertaking, including non-executive members, as well as volunteers and paid or unpaid trainees

and any persons working under the supervision and

direction of contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers.

The Directive provides an extensive personal scope,

which not only includes persons having the status of

worker, including civil servants, but also persons having

self-employed status, shareholders and persons belonging to the administrative, management or supervisory

body of an undertaking, including non-executive members, as well as volunteers and paid or unpaid trainees

and any persons working under the supervision and

direction of contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers.

Most of the countries will have to modify their national law in implementing the Directive, as, while they all

recognise the figure of whistleblower in civil servants,

and almost all - except Austria - include workers under the supervision of contractors, subcontractors or

suppliers, none of them recognise volunteers or people

whose employment relationship has not yet started, or

shareholders. On the other hand, Estonia and Ireland include former employees.

Only Ireland explicitly includes freelancers and, together with France and Estonia, trainees.

Italian law, albeit only for the private sector, includes “persons serving

as representatives or holding administrative or senior

executive positions within the body or an organisational unit of same, and being financially and functionally

independent and persons exercising management and

control of same” and generally “persons subject to their

direction or supervision”. However, the latter definition

is too general and does not allow for it to be established

whether, in the private sector, other categories of workers identified by the Directive are included.

Another overly generic definition is found in the Slovenian Integrity and Prevention of Corruption Act. It applies to anyone who reports any kind of corruption to

the Commission and to officials who report any kind of

unethical or illegal conduct they have been requested

in their sphere of work. Therefore, the law does not expressly identify all of the various categories of workers

to which it applies – except for official persons - but is

generally addressed to everyone (and not only to workers).

From the countries examined, France is undoubtedly the one whose whistleblower legislation applies to the most categories of workers. The Constitutional Council has specified that the Sapin 2 Law procedure is limited to “whistleblowers making an alert against the organisation employing them or the one with which they collaborate in a professional context”. Consequently, the Sapin 2 Law applies to agents, holders or contract staff belonging to the structure subject to the obligation, to trainees and apprentices, as well as to external and occasional collaborators of the administration, bodies or communities concerned, such as voluntary users of the public service who actually participate in its execution, either as reinforcement or by substituting a public official.

3. Reporting channels

The issue of reporting in stages was a highly debated

point in the decision-making process of the Directive.

In the final version, following the amendment proposed

by the European Parliament, the Directive leaves the whistleblower free to select the most appropriate reporting channel. However, it encourages reporting

through internal reporting channels before reporting

through external ones if the breach can be addressed

effectively internally and if the reporting person considers that there is no risk of retaliation.

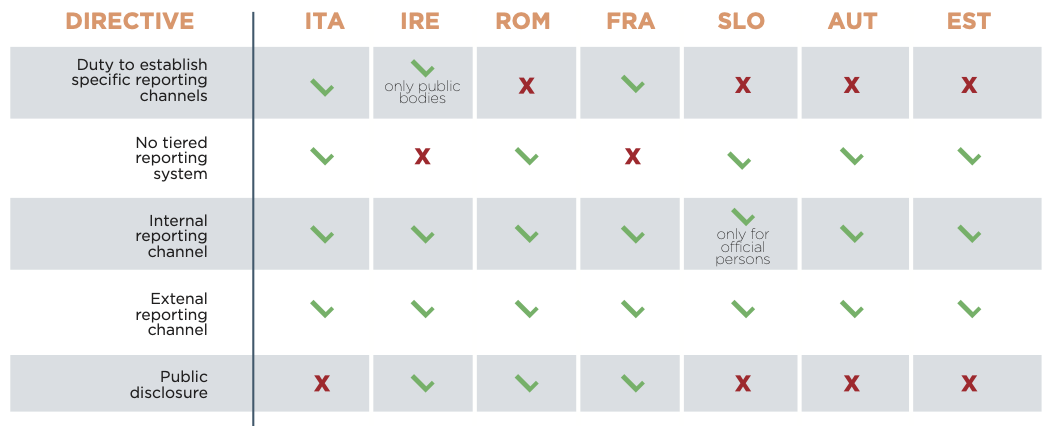

Only Irish (just for the public sector), Italy and French

law provide the duty to establish internal reporting

channels.

- Italian law envisages the establishment of internal reporting channels for all public bodies and, in the private sector, only to those entities that have adopted the so-called 231 models. The adoption of these models is optional, but, if adopted, they must include one or more reporting channels and at least an alternative one with IT methods, which must guarantee the confidentiality of the whistleblower’s identity during the activities carried out in managing the report.

- France and Ireland have a tiered reporting system: whistleblowers must firstly disclose information internally; if this is not possible, or is inappropriate or ineffective, they may report to an external channel. In some circumstances, as a final step, it is possible to disclose publicly.

- In Slovenia, there is a similar reporting system but only for official persons reporting unethical conduct they have been requested. They may report such practices to their superior or the responsible person; if there is no responsible person, or if that person fails to respond to the report or if it is the responsible person himself/ herself who asks that official to engage in illegal or unethical conduct, the report will fall under the remit of the Commission.

- In Romania, a whistleblower may report to the hierarchical superior of the person who has breached the legal provisions, to the Head of the public authority, to the public institution or to the budgetary unit of the person who violated the legal rules. Furthermore, reports can also be made internally to the disciplinary commissions within the public institution to which the person who violated the law belongs.

In some countries, such as Italy, Romania and France,

it is possible to complain to a judicial authority. In Estonia and Slovenia, suspicions about corruption can be

reported to the Police.

In Austria, several public authorities provide reporting systems for whistleblowers, targeting specific areas. The BMI (Bundesministerium für Inneres), the Austrian Ministry of the Interior, focuses on reports on corruption and malpractice (in office); the WKStA (Wirtschafts und Korruptionsstaatsanwaltschaft), the Economic and Corruption Prosecutor, provides a full reporting system, with emphasis on corruption, criminal economic matters, social benefit fraud, balance and capital market offences and money laundering; the FMA (Finanzmarktaufsicht), the Financial Market Supervision Authority in Austria, deals with violations of compliance with the regulations by companies; the BWB (Bundeswettbewerbsbehörde), the Federal Competition Authority specialises in antitrust violations and cases of abuse of market power.

Only Romania and Ireland specifically envisage the possibility of public disclosure. In France, this is only possible as a last resort after the failure of the first two steps or in the event of “grave and imminent danger”. However, the Slovenian Integrity and Prevention of Corruption Act states that reporting to the Commission will not encroach on the reporting person’s right to inform the public of the corrupt practice.

4. Duty of confidentiality

All of the examined countries incorporate the general

principle stated by the Directive in terms of the confidentiality of whistleblower’s identity, meaning that

that identity should not be disclosed without his/her explicit consent to anyone other than the authorised staff

members who receive and/or follow-up on reports. This

requirement is seen in a broad sense, so that it also includes any other information from which the identity of

the reporting person may be directly or indirectly deduced. French law and Italian ANAC Guidelines - however not yet approved - also includes the confidentiality of the identity of the accused person in the context of the alert.

However, there are several exceptions to this principle,

and therefore circumstances exist in which the identity

can be revealed.

- In Romania confidentiality is always granted if the person involved is the hierarchical superior or has control, inspection and evaluation responsibilities over the whistleblower. If the report concerns corruption, forms assimilated with corruption, abuse while on duty and similar offences, crimes against the financial interests of the Union, or forgery, confidentiality is guaranteed.

- In Italy confidentiality is guaranteed only until the end of the preliminary investigation in the context of criminal proceedings and until the conclusion of the evidentiary phase in proceedings before the Court of Auditors. In the context of disciplinary proceedings, the whistleblower’s identity may be disclosed if the complaint is based, entirely or partly, on the report, and the knowledge of his/her identity is necessary for the accused’s defence, but only with the whistleblower’s consent.

- In Austria, in legal proceedings, whistleblowers must disclose their identity as they will be named as a witness in criminal court proceedings and, therefore, their names will be disclosed to the lawyers representing the defendant.

- In Ireland, the protection of the whistleblower’s identity will not apply if the disclosure is required by law or it is essential for the effective investigation, the public interest, or to prevent crime or risks to State security, public health or the environment.

- In Slovenia, the State Prosecutor, the Police and the Court will safeguard the identity of the whistleblower, unless his/her identity is necessary to safeguard the defendant’s right to a fair trial, and if the disclosure will not place the whistleblower or his/her family in any kind of danger.

However, none of the countries examined appears to adopt the appropriate safeguards envisaged by the Directive. In particular, the Directive states that the reporting person shall be informed before his or her identity is disclosed unless such information would jeopardise the investigations or judicial proceedings.

5. Protection measures, burden of proof and sanctions

Only France, Slovenia, Italy, and Ireland prohibit any form of retaliation against whistleblowers

for reasons directly or indirectly related to the report.

This is seen in a broad sense, in accordance with the

Directive, meaning that a whistleblower cannot be dismissed, sanctioned, moved or damaged by any other

adverse effects on his/her working conditions.

Only France, Slovenia, Italy, and Ireland prohibit any form of retaliation against whistleblowers

for reasons directly or indirectly related to the report.

This is seen in a broad sense, in accordance with the

Directive, meaning that a whistleblower cannot be dismissed, sanctioned, moved or damaged by any other

adverse effects on his/her working conditions.In France, Italy, and Ireland, in the event of such measures being taken, they are void by law. The judge may

order the reinstatement of any person who has been

dismissed, not had his/her contract renewed or has

been revoked in violation of the legal provisions prohibiting retaliation measures; severance pay may also

be applied if the employee does not request reinstatement or such a measure is impossible.

It is only in Slovenia and Ireland that whistleblowers

have the right to claim compensation from their employer for the damage caused illegally if they have

been subjected to retaliatory measures as a consequence of filing the report. According to the Estonian Civil Service Act, employees are granted the right to

claim compensation from their employer if they have

been punished or illegally dismissed from office.

The Irish Act provides immunity from most civil actions for damages (except for defamation actions).

French, Italian, and Irish law provide the absence of

criminal liability for disclosure of legally protected

secrets if the disclosure of the information is necessary

and proportionate to the interests involved, if it is made

following the reporting procedures defined by law and

if the person meets the criteria for determining a whistleblower.

Several countries, such as Italy and Slovenia, strengthen the protection of whistleblowers by imposing pecuniary sanctions on those who have adopted retaliatory measures.

In the Italian private sector, disciplinary sanctions are provided for those who violate the measures protecting the reporting person. Furthermore, in Italy, ANAC may apply an administrative pecuniary sanction against the responsible party which has not established procedures for making and managing reports or which has established them, but the same do not comply with what is outlined in the law and which has failed to control and analyse the reports received.

In France, the offence of obstructing the alert is punishable by imprisonment and/or a criminal fine, which is increased when the investigating judge or chamber receives an abusive libel complaint against a whistleblower. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, in Slovenia and France, a breach of the whistleblower’s confidentiality can lead to a sanction. In Italy, Slovenia, Ireland and France sanctions also apply for malicious disclosures.

In France, they may be criminal sanctions (imprisonment or a criminal fine), disciplinary sanctions or dismissal for fault. Conversely, in Austria, Romania and Estonia, no sanctions are provided. However, although Romanian law stipulates no sanctions against retaliation or discrimination, disputes that regard work or working relations may be subject to court review which may subsequently cancel any sanctions applied in the wake of a public interest notification.

As a further protection measure against retaliation, Italy, Slovenia, France, and Romania, in line with the Directive, provide a reversal of the burden of proof. In proceedings before a Court or other authority relating to detrimental effects suffered by the reporting person, and subject to that person establishing that he or she reported or made a public disclosure and suffered damage, it shall be presumed that the detrimental effect was a result of retaliation for the report or public disclosure. In such cases, the person who applied the detrimental measure must prove that the measure was based on reasons unrelated to the report.