Impact Evaluation. The case of the European project Woodie

| Sitio: | Mooc |

| Curso: | M.o.o.c. Woodie - Whistleblower & Open Data |

| Libro: | Impact Evaluation. The case of the European project Woodie |

| Imprimido por: | Utente ospite |

| Día: | lunes, 8 de diciembre de 2025, 16:06 |

Descripción

1. Outline of Impact Evaluation

1.1. Introduction and key concepts

Impact Evaluation (IE) is a relatively recent field of research that inherits the knowledge of different disciplines such as social science, sociology, statistics and econometrics.

It is a specific type of evaluation used for:

- demonstrating the impact of a policy by measuring changes in short term, intermediate and long-term outcomes

- determining whether changes in outcomes can be attributed to the policy

- comparing relative impacts of policies with different components

- identifying the relative cost-benefit or cost-effectiveness of a policy

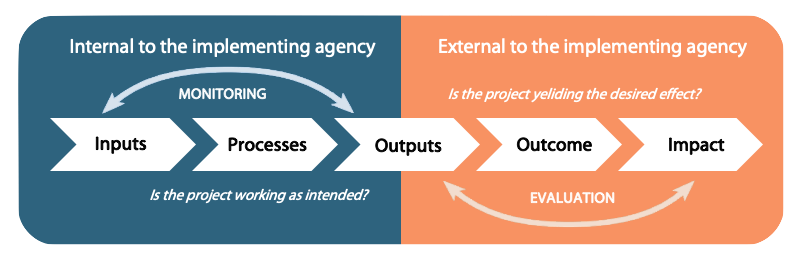

The focus on changes brought about by a policy is at the core of the IE, which intervenes after the implementation phase of a policy as shown in the picture below.

The focus on impact makes crucial to understand clearly its meaning. The concept of impact is very challenging and complex by nature. How impact is defined necessarily determines the scope and content of the impact evaluation because different definitions put emphasis on different aspects of impact, imply different concept of causality (what produces the impact) and how to measure the impact (evaluation design).

In literature, there are several definitions of impact provided by different institutions and organizations, each of them with strengths and weaknesses. The most widely shared definition is that of the OECD-DAC related to development interventions, which defines impact as “the positive and negative, primary and secondary effects produced by a development intervention, directly or indirectly, intended or unintended” (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development – Development Assistance Committee Glossary, 2010).

- stresses the importance to search any effect, not only the expected ones;

- recognises that effects may be positive or negative;

- recognises that effects of interests are produced (or caused) by the intervention;

- suggests the possibility of different kind of links between all kinds of development intervention (project, program or policy) and effect;

- focuses on the longer-term effects of the development interventions.

- evaluating the positive and negative, primary and secondary long term effects on final beneficiaries that result from a policy or an intervention;

- assessing the direct and indirect causal contribution claims of the policy to such effects whether intended or unintended;

- explaining how policy contribute to an effect so that lessons can be learnt.

The primary purpose of IE is to determine whether a policy (or program, project, intervention according to the specific case) has an impact on a few key outcomes and, more specifically, to quantify how large that impact is. It puts emphasis on long-term effects as well as on the search of cause and effect relationships between policy and results. It also acknowledges the logic of attribution (= the idea that a change is solely due to the policy or intervention under investigation) as much as contribution (= the idea that the influence of the policy or intervention investigated is just one of many factors which contribute to a change). This latter aspect is notably relevant for policies that address issues with a complex and multidimensional nature or are multi-actor as in the case of the policies addressed by the project Woodie or in specific circumstances including impact evaluation applied to development interventions.

1.2. Evaluation criteria and methods

- Relevance (= is the intervention, policy, project doing the right thing?): The extent to which the objectives of an intervention are consistent with recipients’ requirements, country needs, global priorities and partners’ policies. Relevance means the extent to which a development intervention was suited to the priorities and policies of the target group, recipient and donor.

- Coherence (= how well does the intervention, policy, project fit?): it is about the compatibility of the intervention with other interventions in a country, sector or institution.

- Effectiveness (= is the intervention policy, project achieving its objectives?): The extent to which the intervention’s objectives were achieved, or are expected to be achieved, taking into account their relative importance.

- Efficiency (= how well are resources being used?): The extend to which the intervention delivers, or is likely to deliver, results in an economic and timely way.

- Impact (= what difference does the intervention policy, project make?): the extend to which the intervention has generated, or is expected to generate, significant positive or negative, intended or primary and secondary long-term effects produced by the intervention, whether directly or indirectly, intended or unintended.

- Sustainability (= will the benefits last?): The extend to which the net benefits of the intervention continue or are likely to continue beyond its termination.

2. The Project Woodie: an impact evaluation experience

2.1. The project and the impact evaluation objectives

“Whistleblowing protection and open data impact. An implementation and impact assessement” (acronnym Woodie) is a project funded by the EU Directorate-General Migration and Home Sffairs under the 2017 Calls for Proposal on corruption. The consortium includes the University of Turin (Italy - lead), the Vienna Centre for Societal Security (Austria), the University of Angers (France), the NGO Amapola (Italy), the Romanian Center for European Policies (Romania), and the University of Maribor (Slovenia).

The 2-years project (2019-2021) focuses on open data and whistleblower protection, two measures identified by the EU, the OECD and many international NGOs as crucial to reach transparency and integrity in public procurement and to deter and detect corruption as well.

Althought the EU, international institutions such as the OECD and the Council of Europe, and Non-governemental organizations at local and global level have recognised whistleblower protection and oper data as key tools to address corruption, there has been no assessment of the impact of these measures adopted by Member States or by European agencies and institutions. The project intends to fill in this gas. It aims to assess the implementation and the impact of these measures in some significant Member States in order to develop an impact assessment model that will be operationalized through an ICT tool for public authorities across Europe.

For more information, go to the project website.

The impact evaluation’s objectives are twofold: on one side, to analyse and understand, at national and European level, the impacts foreseen by the legislators in framing the legislative frameworks on whistleblowing protection and open data policy; on the other, to understand which measures, tools and mechanisms could more effectively facilitate the implementation of the anti-corruption measures within public authorities.

The evaluation questions for designing the evaluation process are as follows:

- To what extent and how the anticorruption misures - WB and OD - contribute to (cause-effect and descriptive question) reaching the expected results?

- To what extent do the stakeholders evaluate the impacts of the measures and agree on the causal processes to explain the impacts achieved/not achieved? Other linked questions are: are the results those that are expected? Are the stakeholders’ expectations on the results satisfied with the results achieved?

- To what extend are expected changes materialise? This question implies checking results against expert predictions; in other words, it means checking if predictions on the outcomes of whistleblower protection and Open data policy happen over time and under which conditions.

2.2. The evaluation activities

The impact assessment work carried out throughout the 2-year project was the result of the following activities:

♦ Research on the legal frameworks on Whistleblowing protection (WB) and Open Data (OD) policy. The activity consisted in analysing the legal framework on WB protection and open data in all the partner countries involved. The research focused on factors that pushed for the adoption of the legislation, its evolution, strengths and weaknesses identified by scholars and practitioners. In both cases, attention was paid to highlight also the connections with public procurement processes. Whistleblowing protection and opne data are unanimously recognised as key measures to deter and detect corruption in public procurement.

♦ Implementation evaluation on the Whistleblowing protection and Open Data legislation. The analysis was conducted at country-level through study cases. Study cases involved 3-5 public authorithies for each country selected according to predefined criteria. Selected organization belong to different typologies of public bodies such as university, ministry, local municipality, state-owned company. The in-depth analysis allowed highlighted how both these measures work in practise and which are the facilitating factors or barriers in the actual implementation of the two anti-corruption measures.

♦ Identification of the Theory of Change (ToC). Through qualitative methods the evaluation team identified, for each measure, the long-term objectives, the core components of implementation that are most likely to have impact and the potential causal links (cause and effect relationship) most relevant for partners’ contexts.

♦ Identification of variables and indicators on the legislative framework (predictive indicators) and actual implementation (implementation indicators). Based on the Theory of Change developed, a preliminary frame of both predictive and implementation indicators for WB and OD was identified. Predictive indicators are indicators whose presence strengthens the possibility of creating impacts. Indicators of implementation are indicators that assess if and how the legislative measures on WB and OD are implemented in the daily activity of public authorities.

♦ Review and harmonization. After a review work, the definitive frame of indicators on WB and OD with corresponding weight values was delivered to partners. This frame constituted the core of the impact assessment model and it contained two sections, one for WB, the other for OD; for each of them, the model comprised the predictive and the implementation indicators.

♦ Elaboration of the online assessment tool. This activity consisted in the design and develpoment of the online tool suited for public authorities according to the impact assessment model developed. The model was adapted to provide them with a concrete tool to self-assess the impact of the WB and OD measures that can be used beyond the end of the project, and thus fostering the culture of anti-corruption in the public sector.

3. The online self assessment tool

3.1. What is the self assessment for?

The project Woodie intends to develop a ICT tool promoting an integrated approach to measure progress in preventing, detecting, prosecuting and sanctioning corruption and to assessign impact of corruption and of anti.corruption measures.

Since the elaboration phase, it was decided to focus the impact evaluation on the public sector and particularly on the area of public procurement. The choice depended on several factors: the economic relevance of the public procurement area, the high risk of corruption present in public procurement across Europe, the role of local authorities on the use of public funds, the impact of such corruption on communities and people’ life. Corruption in public works and infrastructure has the obvious potential for harm to the public interest, add substantially to the costs of public goods and services, leads to the misallocation of public resources, weakens policymaking and implementation, and destroys public confidence in the government.

The availability of better and more accessibile data and the establishment of an effective protection reporting mechanism able to protect whistleblower agaisnt retaliation are two main means to reach trasparency and integrity in public procurement.

Providing public authorities with an online tool to measure both the impact of WB and OD measures and the level of actual implementation can contribute to increasing the public sector capacity to prevent, detect and combat corruption.

The online self-assessment tool has been designed to help public authorities to:

- self-assess their level of awareness on their legislative framework on whistleblower protection and open data

- find out if they have the necessary system in place to fully implement obligations, achieve results and measure over time progresses on the implementation

- serve as a basis for knowledge improvements among internal key staff

- provide feedback on areas, mechanisms and procedures that need to be strengthened in order to improve the functioning and maximize the impact of the two measures towards employees, stakeholders and citizens.

Each section is composed by two distinct self-evaluation questionnaires:

- the first part covers the legislative framework and it means to understand its aims, sectors of coverage, means of implementations, allocation of responsibilities and resources and other relevant features. This part is compiled at the first access and then it is expected to remain unchanged. However, it can be revised it in specific circumstances e.g. in case of adoption of a new law or of significant law amendments

- The second part focuses on how the measure (open data or whistleblowing protection) is implemented within the organization, the procedures and actions adopted and the results obtained. As this part is strongly linked to the day-to-day activities of the organization, it should be repeated periodically to check the improvements.

It is available in all the six languages of the consortium plus English (Italian, English, Slovenian, Deutch, French, Romanian).

3.2. How does it work

The online self-assessment tool is targeting public sector in European countries, it applies to all kinds of public administrations, no matter of the scale or mission. Therefore, it can be filled by civil servants (managers/officers) in charge of tasks and responsibilities in the area of whistleblowing and/or of open data.

Once register, the person can start filling in the questionnaires depending the the thematic sections chosen. They can be completed all or alternatevely according to the user’s function.

For each thematic section – Whistleblower protection or Open Data – the online proposes 2 questionnaires. One is about the levelof knowledge of the legislative framework, the other is focusing on the mechanisms and processess of implementation.

The online self-assessment contains a scoring system to systematize the evaluation and provide respondents with a final score and brief feedback on which areas need to be strengthened in order to improve performance and impact of the measure within the organization.

Feedback are provided both for the questionnaires on the country legislation and for the questionnaires on the implementation of WB and OD measures within each organization but with different systems.

Feedback on the legislative context aim at providing respondents on his/her actual level of knowledge on the legislative provisions on WB and OD measures existing in his/her country. When respondents end the questionnaire, the system shows a summary of the results obtained. It provides two information: the overall score obtained out of 100 (i.e. 60%) and scores in respect to each of the main areas of analysis of the legislative assessment. Answers are broken up into the main areas of analysis and expressed as a percentage of the expected maximum score of each area.

Feedback on the level of implementation and impact within each single public administration are more descriptive. According to the final score obtained, there are four ranges corresponding to four progressive profiles, from poor implementation to successful implementation.

Each profile presents a short description that allows respondent to understand which are the critical areas and identify areas for improvements. As the self-assessment is done periodically, the online tool allows register variations in the scores obtained and therefore the impact of mitigation measures adopted to improve the implementation.

4. To learn more about Impact Evaluation

This section contains additional resources: firstly, a

simplifies glossary with a shortlist of definitions relevant to impact

evaluation, and secondly useful references and materials.

4.1. Glossary

Baseline. The state before the intervention, against which progress can be assessed or comparisons made. Baseline data are usually collected prior to the start of the intervention to assess the before state, or at least at the very beginning of the intervention. The availability of baseline data is important and in planning the evaluation much attention should be paid at this.

Causal attribution. Causal attribution investigates the causal links between a program, policy or intervention and observed changes. Causal attribution is an essential element of impact evaluation. It enables an evaluation to report not only that a change occurred, but also that it was due, at least in part, to the program, intervention or policy being evaluated.

Causal link. The correlation between a factor and an outcome.

Evaluation. A periodic, objective and systematic assessment of an ongoing or completed project, activities, policies, their design, implementation and results. The aim is to determine the relevance and fulfilment of objectives, developmental efficiency, effectiveness, impact and sustainability.

Ex ante impact evaluation. An impact evaluation prepared before the intervention takes place. It predicts the likely impacts of an intervention, program or project to inform resource allocation. Ex ante designs are stronger than ex post evaluation because of the possibility of considering all necessary factors of context, methods and baseline data from both treatment and comparison groups.

Ex post evaluation. An impact evaluation prepared once the intervention has started, and possibly been completed.

Impact. In the context of impact evaluation, an impact is a change in outcomes that is directly attributable to a program, program modality or design innovation. Impact evaluations typically focus on the effect of the intervention on the outcome for the beneficiary population.

Impact evaluation. An evaluation that provides information about the impacts produced by an intervention by understanding the causal link between a program or intervention and a set of outcomes. It goes beyond looking only at goals and objectives to also examine intended and unintended impacts.

Intervention. It is the focus of the impact evaluation. It can be a program, project, policy to be evaluated.

Mixed methods. The use of both quantitative and qualitative methods in an impact evaluation design.

Monitoring. The continuous process of collecting and analyzing information to assess how well a program, project or policy is performing. Monitoring usually tracks inputs, activities and outputs, only occasionally it includes also outcomes. Monitoring data provide essential information for the evaluation.

Process evaluation. A type of evaluation which examines the nature and quality of implementation of an intervention, program or project. It is done during the implementation and it can use different methods including checking that implementation meets standards, cycles of quality improvement or document innovation.

Theory of Change. A theory of change explains how activities are understood to produce a series of results that contribute to achieving the ultimate intended impacts. It consists of laying out the underlying causal chain linking inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts, and identifying the assumptions required to hold if the intervention is to be successful. It should be the starting point in every impact evaluation.

Outcome. A result/effect that is measured at the level of program, policy, or project beneficiaries. Outcomes are results to be achieved once the beneficiary population uses the project outputs. The can be affected both by the implementation of a program, policy or project (activities and outputs delivered) and by behavioral responses from beneficiaries exposed to that program, policy or project. An outcome can be intermediate or final (long term). Final outcomes contribute to define the impact.

Output. The tangible products, goods and services that are produced directly by a program, policy or project’ activities. The delivery of outputs is directly under the control of the program implementing actor or consortium. The use of outputs by beneficiaries usually contributes to changes in outcomes.

4.2. References

Garbarino S., Holland J., Quantitative and qualitative methods in impact evaluation and measuring results. Social Development Direct; 2009, available at http://www.gsdrc.org/docs/open/eirs4.pdf

OECD/DAC Network on Development Evaluation, 2019, Better Criteria for Better Evaluation Revised Evaluation Criteria Definitions and Principles for Use, available at https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/revised-evaluation-criteria-dec-2019.pdf

Patton MQ., Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Newbury Park (CA), Sage, 2002

Rogers P., Theory of Change, Methodological Briefs: Impact Evaluation, UNICEF Office of Research, Florence, 2014, available at https://www.betterevaluation.org/sites/default/files/Theory_of_Change_ENG.pdf

Stern, E., N. Stame, J. Mayne, K. Forss, R. Davies, and B. Befani.. “Broadening the Range of Designs and Methods for Impact Evaluations.” Working Paper 38, Department for International Development, London, 2012, available at https://www.oecd.org/derec/50399683.pdf